For the skin of the Baranung, which is played by hand, they would use the skin of a male goat with horns 3 to 5 cm long or a female goat that had given birth seven times.

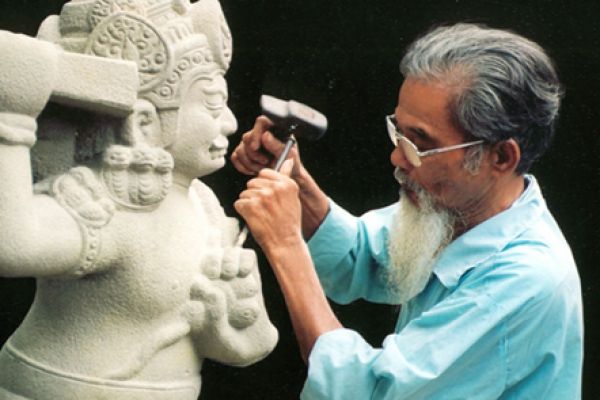

A painstaking craft

In the village of Hau Sanh, located at the foot of Po Ro Me Tower, I was welcomed by Phu Sang, who is the oldest drum artisan there. “Without drums, our festivals would lose their spirit and without the spirit of the festival, the Cham would forget who they are,” he said.

Sang‘s 60-year career started at the age of 15 when he joined his uncles in making drums for local people. At the time wood and animal skins suitable for making drums were plentiful. He and his uncle favoured ironwood, hog plum and shroea obtuse because these types of wood can be used for a long time without cracking, but today this wood is becoming rare enough to find.

For the skin of the Baranung, which is played by hand, they would use the skin of a male goat with horns 3 to 5 cm long or a female goat that had given birth seven times. For the Ginang drum, which is played with hardwood drumsticks, they would use the skin of the Giant Muntjac, preferably a male with black feathers. The skin of the shoulder should be used to make the drum sound more resonant.

Making these drums requires specific technical skills. For example, the string used to stretch the drum head should ideally be cut from the skin of a buffalo with 50cm horns. After it is cut, it must be stretched until it dries along with added salt and ashes for elasticity and durability. Finally, they must decide the length of the drum, which may vary depending on who is to play with. The Ginang normally measures 78cm in length and 60cm for beginners. For the Baranung, 50cm is typical.

However, a traditional pair of Ginang drums must differ by a few centimeters. The bigger drum is placed on the left and represents the female element. It produces deeper sounds and is called the trong ba (grandmother drum). The smaller one is placed on the right and represents the male element. It produces higher sounds and is called the trong ong (grandfather drum). The two Ginang and one Baranung produce three distinct tones when being played together in performance.

Connected with the spirit of the drums

“Every time I make a set of drums, I have to give an offering to the deities and the founders of the craft so that they will protect and assist me. The offering includes three chicken eggs, one bunch of bananas, one bottle of wine and one dish of betel and areca,” said Sang.

The most difficult task for him is to restore old drums, some of them hundreds of years old. “I have to invite the shaman to call up the spirits of the drums,” he continued, “Only after that do I dare fix them. Hardly is there anyone under sixty who dares to make this type of drums.”

Sixty two-year-old Thien Sanh Thiem, another drum artisan from Huu Duc Village, explained to me that this is because Cham musical instruments are full of symbolic meaning. Each set represents a whole person, complete with spirit and emotions.

The Saranai clarion has seven holes, symbolizing a human head with two eyes, two ears, two nostrils and one mouth. The Baranung drum symbolizes a body, the twin Ginang drums are two legs, and the drumsticks are the arms. Finally each Ginang drum skin has sixteen holes through which a string is run to hold it to the body. Two drums bring the total of holes to thirty-two, the number of teeth in a human mouth.

In order to play well, each drummer must connect his spirit with the spirit of the drums. According to Thiem, “If you strike the drum in a superficial way, it will sound out of tune. Playing the Saranai clarion is similar. It sounds completely different from a tower or the stage in a festival. The difference lies in the ability to connect with people’s souls.”

Sang added that “In some villages, there are six sets of drums but no one knows how to play.”

The legend remains

Sang is still strong enough to make about five sets of drums a year. Looking back over sixty years of his craft, he said with regret that none of his children are keen to carry it on. Instead, they all plan to become carpenters, which will bring them more money.

He now lives with his wife in an old house, where he has welcome many foreign reporters and researchers in a tiny room stuffed with drum-making tools. But what makes him most happy are the village festivals and ceremonies. Though he is exhausted after a week-long performance he knows it is still worth it in the end.

“I teach the children how to play drums and clarions,” he said, “so that they can play in my funereal.” His words give me a pang of sympathy, but they are the words of a Cham who conceives of death as simply a trip to the other world.

Thiem has also received an invitation to teach Cham musical instruments in Hanoi. He continues making drums for museums in cities like Hanoi, Binh Dinh, Quang Nam, Phu Yen and An Giang and is very proud that all of his five sons are trying to carve out a good career for themselves by following in his footsteps.

He, in turn, has completed his own father’s wish: “Do not let this craft die, for when there is no longer a Cham song to be heard from villages or towers, there will be nothing left to identify the soul of the Cham people.”