If you asked a tourist to name a network of war era tunnels in Vietnam, no doubt they would say Cu Chi, which is now known throughout the world as a symbol of Vietnam’s dogged determination and military guile during the Vietnam-American war. But there were plenty more underground tunnels built during the country’s struggle for reunification.

In the DMZ, or Quang Tri province, where the bombing was at its most intense – it was declared a free fire zone by the US Army – numerous underground complexes of tunnels and bomb shelters were built to help villagers survive. There are more than 60 tunnels, including the Tan My, Mu Giai and Tan Ly tunnels.

The largest tunnel is called Vinh Moc, which was built to shelter the residents of Son Trung and Son Ha communes. Open since 1985 as a tourist attraction, Vinh Moc is also testament to the endurance, wisdom and bravery of the local population. Rather than flee, 350 Vinh Moc villagers, helped by soldiers serving at the border-post, chose to create a series of interconnected bomb shelters from 1965 to 1966.

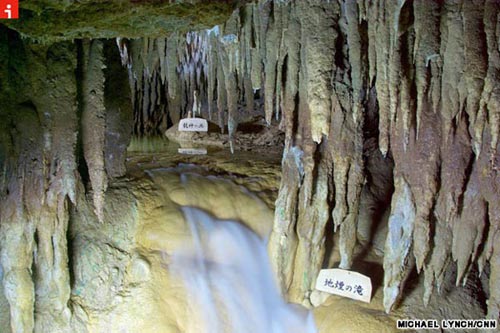

As fate would have it, the soil in this area is a kind of dense clay, which allowed for relatively easy digging. Air also causes this clay to harden, which helped make the walls extremely strong. At first, the system was comprised of two-A shaped tunnels that were connected by a “u-turn”. This initial network would also act as a base to retaliate against the enemy if they landed at Vinh Linh and conveniently as an entry point for supplies to the Con Co Island nearby.

These shelters were then slowly expanded and eventually the entire village was relocated underground. By the end the tunnels had 13 exit and entry points of which seven opened up to the sea, which also helped ventilate the tunnels. Each entrance was propped up by firm wood pillars and covered by trees or bushes. The main trunk of the system was a 768-metre long tunnel. Underground a community of around 60 families survived; there were even 17 children born in the tunnels during the war.

Meanwhile above ground, the area around the tunnels was being pounded with bombs. It’s estimated that there were approximately seven tonnes of bombs per resident in Quang Tri during the war. There were three levels inside the tunnels. The highest level was 8-10 metres down and used for fighting and hiding. The second level was 12-15 metres deep and earmarked for living. The lowest level was at a depth of 30m and used to store ammunition and hundreds of tonnes of rice.

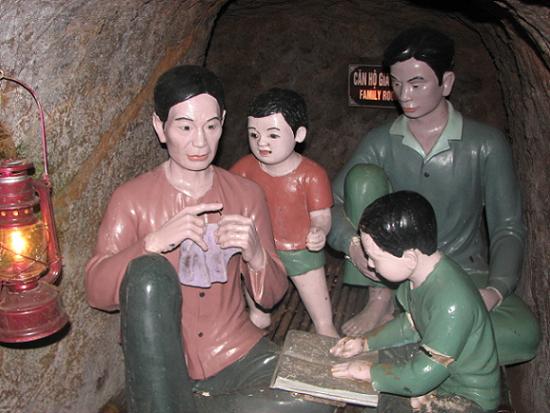

Unlike the Cu Chi tunnels, which were specifically built for military purposes, Vinh Moc tunnels were designed for people to live rather than fight. Inside whole families slept in small chambers – normally about 2m x 1.5m in size – dug on the side of the tunnels. There were larger chambers built as common areas for the underground community: kitchens, storerooms, clinics and other multi-functional rooms.

The tunnels are not just an incredible example of the constructors’ endeavour, but also their meticulous ingenuity. For example, all the kitchens required chimneys, which had to be able to disperse their smoke above ground without attracting the attentions of enemy planes. During the war, most of the women and children and the elderly never saw daylight. But when it was considered safe, they would leave the tunnels under the coverof night to get some fresh air.

Visiting tourists are often left scratching their heads, wondering how people managed to live day to day in such conditions with the mother of all storms raging above ground. Not that is was even safe down below. The US Army also used drilling bombs, which are basically bombs within bombs. The first bomb would detonate and make a crater while the second would then detonate much deeper in the ground and, therefore, potentially destroy an underground tunnel.

Amazingly, the Vinh Moc tunnel system was only hit once directly and fortunately nobody died. Even without the threat of the bombs it was dangerous. In periods of heavy rain, the tunnels could flood and in this damp, muddy underworld sicknesses were also inevitable. Today you can clamber down into the tunnels to get a sense of how people lived during the war. The tunnels are lit at infrequent intervals by weak bulbs and shuffling behind someone blocks whatever little light there is.

The stairs are rough, narrow and steep. Your shoulders scrape against the walls. I find it intensely claustrophobic and suffocating and, of course, I know it would have been far worse during the war. At one stage I pause to stare at some mannequins, designed to represent the wartime tunnel dwellers, and the group leaves me behind. Embarrassingly I am terrified and I shout out until the tour guide returns to help me catch up. We pass some living quarters, which look deep enough for one short person to lie down in.

In one nook a mother nurses a baby. In the next a midwife helps a woman give birth. Elsewhere soldiers clean their guns and rest. At one point the tunnel widens into a meeting room, which also doubled as a school. I picture how people sedately huddled together as the bombs pounded the earth above their heads. It is a chilling vision and I’m happy when the tour group shuffles towards the exit. Finally we emerge into the fresh air.

The blue waters of the give off a wonderfully refreshing breeze. How sweet it must have finally felt for the villagers when they could finally resettle above ground after years in the tunnels. It wasn’t until after 1973, when forces had departed, and the country battled to liberate the south, that the Vinh Moc site could be completely abandoned.

After 1975, it was quickly recognised by the State as playing a crucial role in the war effort and declared a cultural and historical relic that needed to be preserved. The tunnels have been partially restored and reinforced so there is no fear of them collapsing. Today many of the people who borrowed down into the earth still live in the area. Of course, I wouldn’t think they feel the need to visit their old home.